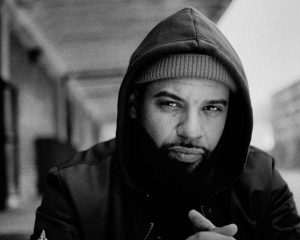

“Trop à perdre, mais j’suis prêt à tout miser” (“I’ve got too much to lose, but I’m ready to go all-in”) proclaims Imposs at the very beginning of his third album, Élévaziiion (société distincte). Two decades after saying essentially the exact opposite as a member of Muzion (on the track Rien à perdre [nothing to lose]), the Québécois rap pioneer shares his revealing evolution in that single opening sentence.

“The difference between me then and me now is that I’m a more accomplished and balanced person. I have a family, I make a good living, I’m happy… In short, I have a lot more to lose than back then, but I’m still going all-in,” says the charismatic rapper. “I’m convinced of my potential and, above all, I don’t seek validation or approval from others. I have something to bring to the table.”

“The difference between me then and me now is that I’m a more accomplished and balanced person. I have a family, I make a good living, I’m happy… In short, I have a lot more to lose than back then, but I’m still going all-in,” says the charismatic rapper. “I’m convinced of my potential and, above all, I don’t seek validation or approval from others. I have something to bring to the table.”

Eight years have gone by since this album’s predecessor, Peacetolet, was released to a lukewarm reception. But back then, Québec’s rap scene was barely poking its head out of the water after a dark period without anything remarkable. “Hip-hop was dead,” he says adamantly. “We were transitioning to streaming, and no one knew where that was going. I lacked the motivation [to carry on].”

Imposs decided to head back to New York City to work with his friend and colleague Wyclef Jean. He contributed to advertisements, as a rapper, lyricist and producer. “I was on a roll over there,” says the artist, who collaborated with The Fugees on the song “24 heures à vivre…” “In parallel to that, I had writing and directing contracts in Québec, notably for Vrak [a youth-oriented cable channel] and Ubisoft. For about three or four years, I simply didn’t see time go by. I got sucked into the machine, and I just accepted every contract that came my way. The problem was that I was working for others, not for myself. I was under the radar.”

Then came the birth of his daughter Nayla, which totally upended his career plans. “I had to make a choice,” says Imposs. “I carry on with this insane pace, or I try to be as present as possible for her. I tried juggling both for a while, but it was simply impossible. It was going to make me ill,” he admits.

“I didn’t have a plan to come back to music, but I could feel inspiration coming back to me, slowly. The fact that I had to slow down allowed me to do a little introspection. That’s when I realized that although sometimes you think you’re winning, in fact you’re losing. You’re so engaged in getting more that you lose your energy. Business is good, but you have no time for the people around you. Before she was born, I was fully invested and I lived to work. I didn’t sleep, I had anxiety… From that point on, I chose a more centred and effective path to channel my energy.”

It’s around 2016 that music found its way back to him and his ruminations. Québec’s rap scene was going through a renaissance, becoming more mainstream in the media and the industry. That’s when Imposs realized just how much water had flowed under the bridge since the “dark ages” during the turn of the millenium. “I was so surprised to see so much talent,” he says. “There weren’t just one or two good artists like in 2007, but dozens and dozens.”

But once again, the rapper was faced with a dilemma: “Either I do what everyone else is doing, but better… or I do something no one has done yet,” he says. Considering his rich musical and human baggage, Imposs didn’t have to dig very deep to bring something new to the table. All he had to do was write about his prolific career over the last 25 years, during which he represented and defended the scene he holds so dear. Like a bridge between two eras.

But the project ended up taking four years to come to fruition. “I wrote and recorded more than 100 tracks,” says Imposs. “It became the biggest jigsaw puzzle of my life.”

By his side since 2017, the Joy Ride Records team helped him sort through all these songs, just as they did with many of his longtime friends and peers such as Blaz, Dramatik, and his sister Jenny Salgado. “Everyone had their own opinion. I had to take some and leave some. Then I withdrew and meditated on all of that,” says the rapper. “I chose to get back to my roots and show my evolution, my elevation. There’s a lot of people, where I’m from, who don’t see any possibility for growth, or emancipation. I wanted to show them that it is possible to do it without losing one’s integrity.”

In order to perfectly synchronize form and content, Imposs collaborated with about two dozen talented producers, including Major, Banx & Ranx, Ruffsound, Odious Love, Farfadet, and Alain Legagneur – all of whom built a rich and vibrant backbone, with roots in New York’s boom-bap (“Daisy”) as much as in the most recent iterations of trap (“Gaillance”).

The result is an album that feels like the 40-year-old rapper is taking stock. “I’d say it’s more like a retrospection,” he says, dropping a portmanteau of his own that combines “retrospective” and “introspection.” It’s true that Élévaziiion (société distincte) isn’t simply a résumé of his accomplishments; it’s also bears sincere testimony of his emotion. “I didn’t want this to be only about my ego,” says Imposs. “I wanted to show my vulnerable side. I wanted to admit that I could’ve done better, sometimes. I wanted to admit I was wrong, sometimes.”

And through a few more “protest” tracks such as “Jaco” and “J’ai essayé,”, Imposs expressed his desire to be part of the social dialogue. The “distinct society” in the album title refers as much to Québec as the sole bastion of the Francophonie in North America, as it does to his Montréal neighbourhood of Saint-Michel as the incarnation of the marginalized position of the ghetto.

“I come from a completely distinct environment that people barely know,” he says. “As a marginalized person, it’s my right, even my duty, to speak up. But I do it my way, in a unifying manner. I’m speaking to the whole world, not just to the people of my neighbourhood.”