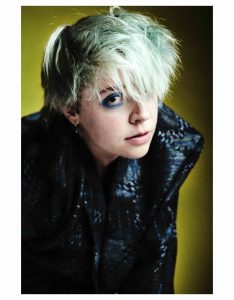

A new revelation on the prolific Québec City music scene, Narcisse is de-constructing some of our most tenacious pre-conceived notions on La fin n’arrive jamais, a concept album where he weaves together electropop, spoken word, and documentary music.

What might come as a surprise, knowing this, is that Jorie Pedneault’s main inspiration for this debut album is a pop-punk album from the 2000s.

What might come as a surprise, knowing this, is that Jorie Pedneault’s main inspiration for this debut album is a pop-punk album from the 2000s.

“I discovered music with Green Day’s American Idiot. It’s a seminal concept album that even became a Broadway musical. It was the middle of the Bush era, and we follow teenagers on a quest for something. They leave the ’burbs to discover the city, and they kinda get lost in all of it. It’s the kind of thing you go through in your early twenties,” explains the singer-songwriter who plays Narcisse.

It’s a project that also includes bassist Michaël Lavoie, saxophonist Frédérique-Anne Desmarais, performer Philippe Després, visual artist Gabriel Paquet, videographer Félix Deconinck, and scenic artist Laurie Foster.

Far from plagiarizing the American trio’s œuvre, Pedneault imagined a concept album, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. A classic concept album, in other words, but based on resolutely contemporary themes, aligned with the concerns that are his mind on a daily basis. “I wanted to de-construct a lot of concepts, including our relationship to gender identity and polyamory, as well as our relationships to heteronormativity and monogamy.”

Another one of the social constructs he de-constructs on the album is the cliché and very romanticized concept of “soulmates.” “We’ve made it romantic, we associate it with love, with someone you’re going to spend your whole life with,” says Pedneault. “But I like to see it another way: you can meet several soulmates in one life. They can be friends or co-workers. The people I’m working with, for example, are soulmates because it made so much sense to meet them when I did.”

Hence the idea of letting those soulmates speak for themselves throughout the album. Totalling 14 songs, La fin n’arrive jamais is punctuated by four short pieces titled “Interstice.” Influenced by the documentary music of Flavien Berger – an artist from France who combined experimental pop and ambient music with minimalist recordings of interviews and narration on his 2019 album Radio Contre-Temps – Pedneault lets the people who gravitate around him speak. “I’ve been working on the album for three years, but it was really this last summer that there was a shift in the angle of the story,” he says. “I started going around and interviewing people with a recorder about the album’s various subjects. In the end, it’s the story of my peers, of my generation’s youth.”

Along the way, Pedneault saw fit to add his voice to these interstitial testimonies, after heeding to the advice of multi-disciplinary artist Olivier Arteau – who’s credited as the album’s playwright. “He really wanted to hear me, like we hear all the others. He wanted to feel the human behind the persona,” says Pedneault.

From this came one of the most beautiful and powerful sentences of the album, heard at the very end of “Interstice C”: “C’est ben beau tomber en amour toujours avec une autre personne, mais calice man, à un moment donné, il faudrait que je tombe en amour avec moi-même.” (“It’s one thing to fall in love with someone else, but for fuck’s sake, man, at some point I need to fall in love with myself.”).

“It’s something I said in the middle of a conversation [and that’s a good representation of the project as a whole],” says Pedneault. “When I started conceptualizing Narcisse, I was wondering if I should play a character that is full of himself. I quickly realized it wasn’t relevant to play such a character in the public space. It became self-evident that Narcisse had to be a vehicle to make people realize that they need to love themselves.”

Beyond the concepts of de-construction, it’s that love of self that sits at the thematic centre of the album. It’s also a way to push back against prevailing violence, especially when it comes to sexual and genre diversity. “Being non-binary existed when this project started,” says Pedneault. “Over the course of the last few years, I changed my pronoun to ‘they’ and my first name to Jorie. It’s a given for people close to me to call me that now. It feels good. But if I’m at the grocery store and the cashier calls me ‘she,’ it will obviously create some violence.”

Narcisse is a response to this violence, even though his intention isn’t fundamentally activist. “We’re just singing about our realities,” says Pedneault. “It just so happens that those realities are political.”

The participation of the band in the finals of the 2020 Francouvertes was an unexpected showcase for the propagation of these essentially political realities. “We’re a project that’s advocating for things, but we know that this kind of offer can close doors,” says Pedneualt. “The Francouvertes gave us the awareness that this project could exist, and that people would be there to receive it. I’m not sure the industry would’ve been ready for all this 10 years ago.”

At the very end of the album, “Devenir fleur” opens a dialogue about Narcisse. Narrated by Gabriel Paquet, the epilogue directly references the Greek myth of Narcissus, the young man so smitten by his own reflection in a pond that he ultimately perishes and becomes a flower.

“There is a feeling of being killed and resurrected,” says Pedneault. “It’s not a coincidence: I felt like I went through that recently. A flower is also a symbol for springtime, because this album marks the end of a cycle, as well as the beginning of something. It’s a calling card that will lead to all kinds of beautiful things in the coming years. It’s our way of saying, ‘Here we are, among you.’”