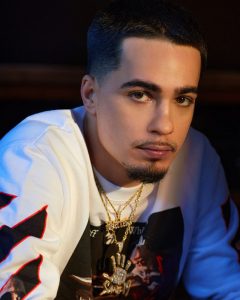

“I’ve matured a lot during the past two years. You can hear it in my music,” says White-B over the phone.

Without being a 180-degree about-face, his second EP, Double Vision, is indeed more composed and deeper than the rest of his work. “I’d somewhat lost my way,” he admits when the subject of his first EP, Blacklist, comes up. “I was too focused on the vibe and not enough on the lyrics. I decided to go back to the basics.”

Thus, Double Vision is more reminiscent of the raw spirit of Confession risquée, his first mixtape, than the smoother approach of Blacklist, an eclectic project with some pop interludes. Apart from Toxic, “a beat that wouldn’t be out of place in a club and that would please everyone,” this new offering is pure White-B: trap beats, simple lyrics, punchy lines, and a precise, melodious flow, able to modulate its intensity with impressive ease.

Yet, any comparison to the early days of White-B stop there. On this third solo project, the member of the 5sang14 crew displays a more concise, homogeneous, and refined artistic direction, the result of a collaboration with talented producers like BirdzOnTheTrack, Alain, and Ruffsound. This playground was conducive for the rapper to let himself go into more raw emotions than he usually does, and distance himself from hard-hitting street stories. Hence the “maturity” to which he refers.

“The main difference is that I earn a living with my music, now,” he says. “That’s probably why I rap less about the street, or at the very least with a more refined approach. I look at it from a distance because I know it’s impossible for me to go back there.”

White-B confides several times on the mini-album, notably on the engaging opening track, “Traine en bande.” “Mes pensées sont noires/Gothiques” (“My thoughts are dark/Gothic”), he professes, as a sign that the last two years weren’t as rosy as his immense success might lead us to believe. “Some nights I can’t even fall asleep,” says White-B. “There’s a million things going through my mind. My spirit is dark,” he confesses. “What people don’t know is that I’m under probation since 2017. It’s like being in jail, but at home. Because of my special status [as a musician], I’m allowed to go out, but only in the presence of a few select people. All that weighs on me, even though my career is going well.”

At the other end of the EP, “Maman ça ira” also refers to his peculiar situation. “That black cloud hovering over me for the last few years also affects my mom,” he says. “I’ve lost track of the number of court appearances where she was by my side. But the good thing through it all is that she sees all the efforts I’m making. I’m 25, I just bought my first house, and within two years I’m going to buy a duplex where my mom and my brother can live. She sees all that I’m accomplishing, and she knows my past is well behind me. She saw the good and the bad and she’s never told me to give up music. She’s always told me to go for it.”

Like many rappers with a torturous path, it’s ambition that keeps White-B afloat. The constant motivation to excel is at the heart of the EP’s themes, as much through its resilient portraits as its odes to the American dream, and money. “Ambition is what guides me,” he says. “A lot of people have tried to run me down, but instead of complaining about it, I use it as motivation. At this point, no one can stop me.”

Like many rappers with a torturous path, it’s ambition that keeps White-B afloat. The constant motivation to excel is at the heart of the EP’s themes, as much through its resilient portraits as its odes to the American dream, and money. “Ambition is what guides me,” he says. “A lot of people have tried to run me down, but instead of complaining about it, I use it as motivation. At this point, no one can stop me.”

The situation is very different from that of a few years ago. While accumulating hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube, the rapper had to live with repeated concert cancellations from skittish promoters, influenced by police warnings. The target audience of the rapper and his cronies was considered unsavoury.

The balance of power changed when White-B and his team began. doing business with serious promoters. In 2018, 5sang14’s sold-out show at Club Soda marked a notable advancement for Montréal’s burgeoning street-rap scene, one whose artists are far from unanimous.

“Even then, the police tried to scare venue’s people… But the demand was so great [that they didn’t succumb to the pressure],” he maintains. “You can’t stop a machine that’s full steam ahead.”

The following year, 5sang14’s performance at the Francos de Montréal in a packed MTelus confirmed the phenomenon. Since then, the squad has signed with one of the biggest hip-hop labels in the province (Joy Ride Records), accumulating millions of views and plays in the process. In the last few weeks, White-B has been awarded two gold singles for his songs “La folle” (with Capitaine Gaza and MB) and “Mauvais garçons” – an honour awarded for the equivalent of 40,000 singles sold (or 6 million streams). “And there’s more coming,” he promises.

The next step will be exporting himself. I want to put the Québec flag on top of the Eiffel Tower, says the Québec rapper on “Traine en bande.”

“The Eiffel Tower is the symbol. I do want to take this to France, but also to Africa. It’s the continent that makes Francophone rap so popular at the moment,” he says. “I want our flag and our local scene to be recognized at the same level as other Francophone rap scenes of the world. We don’t get the credit we deserve, but it’s only a matter of time.”