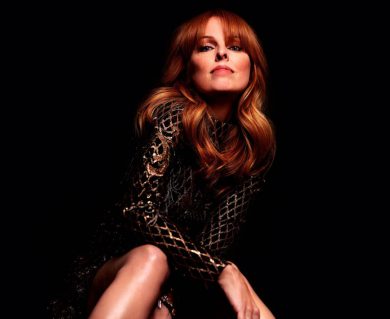

France D’Amour’s 13th album will thrill her early fans: D’Amour et Rock’n roll is raw, an album whose heavy sound grounds the listener while her voice and lyrics soar to the sky.

On October 2, 1994, France D’Amour finished the Rock Le Lait tour at the Montréal Forum, alongside Vilains Pingouins and Jean Leloup. We were there. Animal, her first album, was launched the previous year and Déchaînée would break the sophomore jinx a few months later. The young Mont-Rolland native told the media, back then, “I’m confident enough to not be afraid of standing up to artists like them.”

On October 2, 1994, France D’Amour finished the Rock Le Lait tour at the Montréal Forum, alongside Vilains Pingouins and Jean Leloup. We were there. Animal, her first album, was launched the previous year and Déchaînée would break the sophomore jinx a few months later. The young Mont-Rolland native told the media, back then, “I’m confident enough to not be afraid of standing up to artists like them.”

We were blown away when she sang her anthem “Vivante,” her fist raised and her leg kicking, as if on a mission: “Chanter à tue-tête / Tout ce que j’ai dans l’ventre / Chanter comme une bête / Pour me garder vivante” (“Sing as loud as I can / Everything I’ve got / Sing like an animal / Just to stay alive”). For many of us – despite the artist having shown us a softer side on hits such as “Si c’’était vrai” and “Ailleurs” – this woman is a rocker at heart.

Now, D’Amour returns to her roots with 10 songs recorded at the studio of Jason Lang, her guitarist, with the help of longtime collaborators Patrick Lavergne on bass and Sam Harrisson on drums – “my very own Dave Grohl,” she says. “It was about time, and even though I’ve never stopped playing rock, a woman told me at the record launch, ‘I’ve been waiting for this album for 20 years!’ I thanked her for her patience, I know I took people on a wild ride, in the meantime,” she says about the various musical styles she’s explored over the years, like her two-volume exploration of jazz, Bubble Bath and Champagne.

What’s the difference between the 1993 rocker and today’s rocker? “There’s one helluva difference!” she says. “The rocker back in the day of Animal operated purely on instinct and energy. Now, my energy is more channelled, controlled. There was something truly serious about Animal. Now, nothing’s serious, we don’t give a damn, we just let go and have fun! We were like teenagers, we just wanted to find good grooves, raw and imperfect material. When you listen to albums from the ’70s, there are off-notes, and it sounded more natural.

“I want to stand up on my chair, drive too fast, be too loud!”

“We’d sometimes laugh uncontrollably, as if the music was taking us back to childhood, and we were unlearning what we know. We wondered how we played when we didn’t know how to play. It feels amazing to let go like that, to play any which way. A lot of the songs sound like demos, which drove our producer crazy, trying to fix those imperfections, but we like those songs just the way they are. I was sick when we recorded ‘Tout à gagner,’ my voice is completely off, but I said, ‘let’s keep that!’ Rock ’n’ roll is all about feeling and emotion.”

Straight to the heart, without neglecting the mind, the album is very guitar-driven, and emerges as quite cohesive from repeated, playful elements, without being overly innovative.

“Rock music is perfect when you want to sing about topics such as outrage, which is the case on this new album,” says D’Amour. “I sing about what I’ve realized over the years, my personal life, I reveal a lot about myself. It’s me, right now. There’s not a single love song on the album,” says the newly-single 54 year-old, with a sliver of irony – although it’s worth noting that the last song on D’Amour et Rock’n roll, “T’étais mon père,” is the eulogy she read at her father’s funeral, not long ago.

It’s always in such moments that D’Amour gives the best of herself. She goes on, supercharged: “I want a scrapyard, I don’t feel like being sexy. I want to stand up on my chair, drive too fast, be too loud, turn around and stop only when I feel like it. I need to say, ‘Fuck off,’ and to just let go.”

The first step was duly accomplished during her record launch concert at Coup de cœur francophone. “My armpits were sweaty, but I didn’t fumble a single word of my new songs,” she says. “I’ve got a good memory; apparently Alzheimer’s won’t be [happening] right away in my case. I’m still a teen, inside. Age is all in the mind.”