“Interfacing” is a series of articles about the innovative companies we’re working with here at SOCAN. Ryan Maule oversees this work, focused on finding those companies and integrating them with our services, ensuring that SOCAN members can access the best tools the music tech industry has to offer.

Robin Leboe

Sessionwire is a great company based out of Vancouver, that aims to connect your studio remotely to other studios around the world. Sound like the holy grail? Well, for many music-makers, it’s long been the dream to create and record live with others over the internet, regardless of their geographic location. The obvious benefits of this approach are reduced costs, eliminated travel time, and the immediacy of feedback during a recording session.

This was definitely something that kept musician, producer, SOCAN member, and Sessionwire founder Robin Leboe up at night. While living in the town of Gibsons, B.C. (a 40-minute ferry ride from Vancouver), finding the right collaborators was a difficult task. Not only for himself, but for his family members – who are also musicians and songwriters. After coming up empty-handed searching the web for something that would allow live, studio-quality audio connections with other music creators, Robin finally decided to build something from scratch… and Sessionwire was born.

It took time, investors, and a couple of founding partners to bring the vision to life. Robin sought out longtime friend and Nimbus School of Recording co-founder Kevin Williams, and pro-audio engineering veteran Rick Beaton, to round out the team.

There have been other attempts at this in the past, but Sessionwire takes a new approach to online musical collaboration by providing a live, studio-like, remote production experience for its users. It combines web-based tools and a native macOS app to provide live video and audio connections between their users and their DAWs (digital audio workstations), regardless of the type of recording software they use. The website provides registered users with a profile, and the ability to network and connect with other Sessionwire users anywhere in the world. Once registered, users can associate their account with their SOCAN membership, and show off a SOCAN badge right on their profile.

We’re working with Sessionwire to highlight SOCAN members because we believe that our members are professionals who bring experience and talent to the music-making process. Eventually you’ll even be able to register songs that are produced in Sessionwire with SOCAN, as part of the process.

Sessionwire On-Screen

So, what sets Sessionwire apart from incorporating existing products like Skype and Dropbox into the studio workflow? Says Leboe, “We’re the first to offer a truly live collaboration tool that provides an easy-to-use, studio-style experience that’s combined with a social networking platform for connecting with other music producers around the world. We built Sessionwire to break down barriers between music creators, and to provide them with tools that let them save time, travel, money, and connect with one another in a truly human way.”

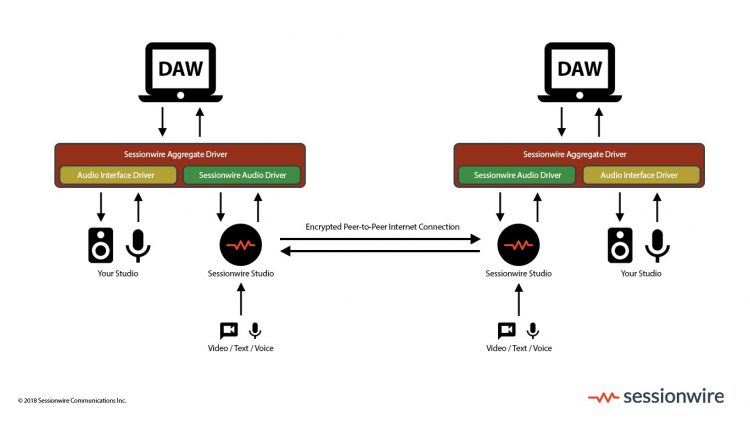

The tools that Robin mentions include being able to stream studio-quality audio alongside video chat, and connect and record into any macOS Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) with drag-and-drop file transfer between Sessionwire users. This is pretty ground-breaking, and we’re not the only ones who think it’s exciting.

Sessionwire Schematic

Columnist Dani Deahl, of the popular tech website The Verge, recently wrote, “From Anaheim, California, I video-chatted with a musician in Vancouver using Sessionwire, and recorded some of his vocals right into the computer I was using, running Pro Tools. This was amazing. Instead of sending recorded files back and forth, I could record a musician live from anywhere in the world, and see them as it happened.”

“Sessionwire looks like a dream becoming real for ‘caveman’ musicians like me.” – Randy Bachman

And then there are industry veterans like Randy Bachman, who says, “Sessionwire will connect the musicians of the world like nothing else before. Sessionwire looks like a dream becoming real for ‘caveman’ musicians like me, who need simplicity to connect on the recording format they’re using – to finally be able to instantly connect and share music files on the internet. I’d love to eliminate sending MP3s via e-mail to other musicians to put into their DAW and have the file changed. Only then, to get their performance sent back to me as an MP3 and have to drop it into my DAW [which is GarageBand]. The fact that you keep Sessionwire live is an amazing approach.”

As most musicians know, working live not only speeds up the creative process because of the invaluable live feedback, it also restores the creative energy and spark that’s lacking in a non-live creative process, like using e-mail and Dropbox. Those who remember the “happy accidents” while working together in a rehearsal space, or traditional recording studio, will relate.

At SOCAN, we’re excited about Sessionwire, and we think this could be a valuable tool in your arsenal. We’d love your feedback, and comments about it, and are looking to ensure that SOCAN’s core services are even more integrated with it in the future. It’s early days, but if this is the future of music production, it sure is bright.

For more information about Sessionwire, visit www.Sessionwire.com and visit the SOCAN Partner page in the secure portal to find out more about the other opportunities we have cooking. If you have any other questions, feel free to contact Ryan Maule at ryan.maule@socan.com.