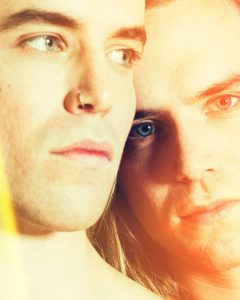

Brothers Simon and Henri Kinkead consider all forms of Migration on their first album. Released last October, its title is directly inspired by said action of leaving a place. With the help of Simon Kearney on production duties, the duo offers ten songs about questioning, life changes that we choose (or are imposed upon us), and the necessary evolution from childhood to adulthood – the kind of concerns that go as well with being in one’s mid-20s as coffee goes with Monday morning.

Birds leave for the winter, but they always come home. The Kinkead twins try to look to the future, mourning what they leave behind. “COVID is putting us through an existential crisis in a context where everyone in experiencing a crisis. It’s become hard to distinguish between the stress that comes from within and the stress generated by the pandemic,” says Henri. The confusion is absolute.

Birds leave for the winter, but they always come home. The Kinkead twins try to look to the future, mourning what they leave behind. “COVID is putting us through an existential crisis in a context where everyone in experiencing a crisis. It’s become hard to distinguish between the stress that comes from within and the stress generated by the pandemic,” says Henri. The confusion is absolute.

“We’re surrounded by anxiety and our society is constantly evolving, not always in the right direction, and it’s OK to question oneself – even though we have to manage a crisis that’s bigger than ourselves,” Simon adds. “It’s not hard to lose oneself, and finding the right balance is hard.”

Today’s young adults grew up with social media, and they defined themselves that way, which exposes them to suffering from overexposure, even in a context of isolation. “For us, then, it’s only normal to sing about what we go through and write very personal songs,” says Simon. Directly addressing other identity issues such as sexual orientation and belonging, they don’t formalize their speech, but say things as they are.

“We’re not trying to provoke,” says Simon. “We don’t pretend to be Hubert Lenoir, but we also know we represent another model of difference. We’re another vector of that message which can only benefit from being shared as much as possible. The more models there are, the better people who don’t feel represented will feel.”

According to Henri, producer Simon Kearney solidified Kinkead’s tenets by providing them with the groovy foundation for their album. “He brought us a stylistic cohesion,” says Henri. “We’re songwriters, we work with voice and guitars. Once we got into the studio, we told him about our inspirations, and he found our sonic identity.”

Although some believe the twins have a sixth sense that allows them to communicate without saying a word, maybe it’s just that they have a somewhat esoteric gift for cohesion. “Our telepathy is simply that we know each other’s limits. We don’t put a spanner in each other’s works because we’re in total symbiosis,” says Henri.

And although the key to their success resides in their common vision, they’re still able to recognize the strengths that distinguish each sibling. “Henri has a better instinct for pop hooks than I do,” Simon readily admits. “I’m more into words, the ways of saying things, and making a text work. Let’s just say I’m more vulnerable and sensitive.” “Simon is the emo half of the band,” Henri adds with a giggle. “We do love bouncing off each other’s ideas, and letting inspiration take us wherever it wants. Like for the song ‘Atomic Suzie,’ I had this idea of a woman in a trance who goes to a karaoke bar and just slays. The idea came to me after jamming on drums and bass.”

Behind the concept of migration lies a notion of the evolution of humans towards an ideal version of themselves, while believing in the necessity to grow in an environment where life is good. “The climate crisis is one thing, but actively participating in the transition towards a political and economic system that will allow us to survive, while avoiding profit flowing only to an infinitesimal portion of the population, has become an absolute necessity,” says Henri. “Instead of allowing only 10 percent of people to go live on Mars, maybe we should strive to provide everyone with drinking water without devolving into a civil war.” “A revolution is something really hard to do,” his brother adds. “We must find a balance between all the things that are important to us, and the things that are necessary for others to live, too.”

Then, after the revolution, or the non-end-of-the-world, the end of the pandemic, one desire will continue: they’ll be playing this music that wants to be a vector for change. “Music exists through exchanging,” Henri believes. “We were lucky enough to be favourably received even without an actual physical record launch. Let’s hope it bodes well for what’s to come. We’re lucky enough to be young, and full of the energy required to carry on. We’re optimistic. We’ll be in full swing when the time comes.” “We’ll just go work at Normandin’s [a family-oriented chain of restaurants in the greater Québec City area] while we feed ourselves artistically,” Simon goes on. “Nothing can stop us now.”